WORLD PREMIERE

World Premiere: May 3, 2011 - La Monnaie, Brussels - Conductor: Pablo Heras-Casado.

Libretto (Ger) by Hannah Dübgen, based on Zeami’s "Matsukaze" (2010).

Commissioned by the Theatre de la Monnaie (Brussels).

NOTES

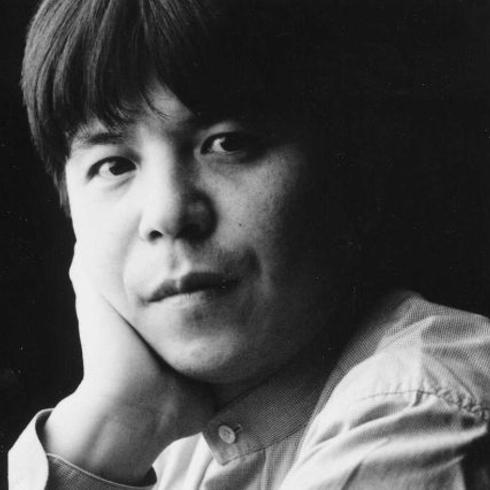

Toshio Hosokawa about his new opera Matsukaze, the N? theatre and the beauty of the transitory.

Ilka Seifert (=IS): Matsukaze, your most recent opera, goes back to a topic of the classical N? theatre that is well-known in Japan. It is a story about two sisters, Matsukaze and Murasame, who are in love with the same man. Since their wishes remain unfulfilled, both of them return again and again as spirits to the living after their death. What are the things that matter to you in this story of the two sisters?

Toshio Hosokawa (=TH): It is a drama of the salvation of souls. Both women suffer a very tragic fate. To me, they are shamans who connect two worlds with one other, the world of the living and the world of the dead. Upon composing, I thought that the two behave like yin and yang, they are like two sides of the same woman, they complement one another. Matsukaze and Murasame return to our world. They have a tragic fate and suffer from the great attachment to a desire of which they want to free themselves. It is the music, the singing and the dancing that redeems them. This is a very important aspect for me personally. By composing, I myself want to get rid of such attachments. This is a religious, very Buddhist matter.

IS: But music often is of spiritual significance not only in the Japanese, but also in the European tradition.

TH: To me, music always has a strong religious aspect. These days, we have lost a lot, we have lost our church, the certainty of faith. It is us artists who convey this redeeming role of the human soul. It is in the arts that many people look for the deliverance from worldly constraints, from strong desires, from these very attachments. I, too, want to cleanse my soul through music.

IS: Your soul or also the souls of the people who listen to and experience your music?

TH: Good music can be liberating to both the composer and the listener. This actually corresponds to our Japanese tradition as to why we practise the arts: ikebana, tea ceremonies, archery, calligraphy, all these arts have the same goal: salvation or enlightenment.

IS: In Matsukaze, this salvation is eventually accomplished through the dance which eventually reunites both women with nature.

TH: In the piece Matsukaze, even the title is important for the name of Matsukaze is a compound meaning wind (ikaze) in the pine trees (matsu). The chant of these women can be seen as sounds of nature. To me, this was a very important aspect of composing; without song, I cannot unite the score with nature. When making music, my sounds become one with the whole cosmos. In Matsukaze, it is the music, the song and the dance that establish this connection with nature.

At the end, Matsukaze turns into wind and Murasame into water and rain – this is a very Japanese way of thinking. Nowadays, we need shamans for we have lost the connection with the dead. We are living in a world from which we want to exclude death. We are forgetting the dead although all of us are going to die. But death is part of our existence. Shamans establish the connection with the world of the dead, they commute between the world of the living and the world of the dead.

IS: Is this what all N? theatre plays are about?

TH: There are quite different N? plays; the most beautiful or most important plays deal with exactly this issue of the disengagement from attachments.

IS: In Matsukaze, salvation is eventually accomplished by an ecstatic dance which unites the sisters with their beloved for the last time in a vision.

TH: Yes, but Japanese dance is totally different from European dance. European dance often fights gravity.

IS: Now you are referring primarily to the classical ballet. For Sasha Waltz who will choreograph and produce Matsukaze, it is especially the perceptibility of the body, its weight, the breath or the movements that play a special role.

TH: This is why I work with her.

IS: The N? theatre is a very strict, ritualised stage art with extremely slow, calculated movements. This artificial character is in contrast to your music which, in my opinion, develops quite organically.

TH: These strict movements and principles date from the time of origin of the N? theatre. At that time of the Samurais, the society was very strict and extremely hierarchical. I absolutely dislike this side of the N? theatre, it rather bothers me. But the idea, the main theme, interests me. In many Japanese arts, e.g. kabuki, I recognize a very strict social order. I see a hierarchy, a male-dominated society and very strict laws. It is almost impossible to breathe. I want to free myself and the arts from it.

IS: Matsukaze is your third work for music theatre. In early 1988, Visions of Lear dealt with Shakespeare whose influence on the European theatre may be compared to that of N? for Japan. A Japanese team produced and performed it on the Munich Biennial. In 2004, Hanjo was the first work to deal with an original topic of the N? theatre, though in the adaptation of a 20th-century Japanese poet. Matsukaze is based on a German libretto by Hannah Dübgen which, deliberately, adheres closely to the 14th-century text by Zeami.

TH: I have always been lucky with the artists with whom I have worked together. In my first opera, it was Tadashi Suzuki. He studied the Japanese theatre very carefully and thus found his own new theatre form. The second opera Hanjo was based on a topic from the N? theatre. Yukio Mishima had reinterpreted the text in the 1950s. In this production, I worked with Anne Teresa de Keersmaeker which happened by chance for the Festival in Aix-en-Provence had chosen the both of us and brought us together. We had known each other before already, I had composed a little dance piece for her and she had interpreted it beautifully. And this is the third opera, this time with a real N? theatre play. I absolutely wanted to work with Sasha Waltz, this was my personal wish. I know her works and think that she could really find something new in this topic and develop something new from the original N? theatre.

IS: You saw Dido & Aeneas, Sasha Waltz’s first choreographic opera which reformulates the idea of the opera as 'Gesamtkunstwerk' in a very impressive way. Here, dance and song, language and music coalesce in a completely new and close way.

TH: In the European opera, music and movements are usually separated from each other. The singing is beautiful but the air is always the same. If you come from the Japanese theatre, you are used to the fact that singing and movement are always related to each other. The European opera is very realistic but when you watch it, it becomes boring. I would like to develop something new, an absolutely new opera. To do that, I absolutely need new impulses and people like Sasha Waltz.

IS: Like other N? theatre plays, Matsukaze is based on an aesthetic concept that is rather strange to the European way of thinking and on a concept of time which allows past, present and future at one moment. How would you describe this concept?

TH: Flowers are a good metaphor. Flowers are also used in ikebana. Flowers die within a short time, they show us the transitoriness of life. If flowers would be there forever, they would no longer be beautiful. Since they wither, they show us how beautiful and precious life is. In his aesthetics, Zeami tried to describe the outstanding N? actor as 'flower'. This corresponds to our Buddhist way of thinking: Transitoriness is beautiful. And so is music. It sounds but always disappears quickly. Music is beautiful because it always lives in the respective time. It remains in one's heart, but it is fleeting. It's the same with Matsukaze – an event is unique and always followed by death, silence, emptiness, space, and this is why everything that we do has to be beautiful. In the art of ikebana, we cut the flowers which will lead to their death. We know that they will stay with us for only one or two days but this is the reason why we think the flower is beautiful. You know our Japanese cherry blossom; it only lasts five days and then fades away like the rain, so beautiful. In contrast to the art of the West which tries to grasp the eternity and permanence of beauty, here you find beauty in the sadness of a life that withers and dies.

IS: How do you see your own role as an artist between two cultural worlds as different as Japan and Europe where you live and work?

TH: We need other ways of thinking and musical material from the outside for we cannot make any progress solely on the basis of the Japanese way of thinking. I need them both, music from Japan and music from the rest of the world. I love European music more than Japanese music; as a child, I studied European music already. Almost all Japanese love European music because it opens a wide space. The Japanese space is quite narrow. I regard our Japanese music as less independent. It is not just an individual piece of music, it is not just pure music. Our music needs atmosphere, context, climate and special places in order to exist, and it is only through the combination of these components that it becomes alive. European music, on the other hand, is an abstract space, a big world. You can separate the ground from this space and use it in a different context. This is impossible with Japanese music which is always part of a ceremony or associated with certain places. This is different with European music: You can also listen to Beethoven in a temple; it is a music conceived from sounds, and the musical idea is very strong.

© Salvation through music