" Deep time "

For orchestra

Boosey & Hawkes

SÉLECTION 2018

- Nominated for : The Young Audience Prize 2019

- Nominated for : The Musical Composition Prize 2018

Deep Time was conceived as a companion to The Triumph of Time (1972–2) and Earth Dances (1985–6) with which it shares an interest in time and geology. Uniquely, however, the musical processes in Deep Time are comparable to the notion of geologic time first proposed by the eighteenth-century Scottish geologist James Hutton (1726–97). According to Hutton, geologic time involves a perpetual cycle of rock erosion, sedimentation and formation for which there is ‘no vestige of a beginning, no prospect of an end’. This suggests an unimaginably slow process, a kind of sustained bedrock, which is present in Deep Time. But in geologic time there are also catastrophes, volcanic eruptions, resulting in a kind of chaos or frozen violence. Similarly, in Deep Time one kind of multi-layered order is superseded by another as various instrumental voices, heterophonic lines, hocketing textures and other objects follow, overlap, or are juxtaposed in a discontinuous yet related succession that is in a permanent state of exposition.

Deep Time is not a representation of Hutton’s ideas, however: it is about itself, about the perception of musical time and how long the piece lasts. In tonal music our sense of the work’s length is influenced by harmonic rhythm, which moves differently in a Haydn or Schubert symphony. But is there an equivalent in music that lacks tonality? Fundamental to Deep Time is a tension between clock time (Barenboim requested a piece lasting fifteen minutes) and the potential duration of musical ideas, of which there are enough in Deep Time to last over an hour. A piece of music occupies a fixed duration, as a painting sits in a frame, but a musical idea has its own speed, like the elephant in the procession depicted in Breugel’s The Triumph of Time. Similarly, geologic time is measured in years but has its own tempo.

Hutton was not the first to consider deep time – Leonardo da Vinci had noticed marine fossils on mountaintops and wondered how long it took for rivers to carve out valleys – but he was the first to intuit the Earth’s colossal age. The term ‘deep time’ came later, coined by James McPhee in his 1981 book Basin and Range. By then the Biblical idea of the Earth as 6,000 years old had been replaced by the current estimate of 4.5 billion years. If deep time is equivalent to the old English yard – the distance from the King’s nose to the end of his outstretched hand – then, McPhee observes, ‘one stroke of a nail file on his middle finger erases human history.’

There is violence in geologic time but also calmness after the event as experienced when viewing a landscape, for example on the island of Raasay off the west coast of Scotland. Here, where The Mask of Orpheus was composed (1973–83), some of the Earth’s oldest rock sits next to some of the youngest, the isolated fragment of a deeper process, a broad geological fault line. As in Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, stillness in Deep Time does ‘not in the last resemble a peace’. Rather, it is ‘the stillness of an implacable force brooding over an inscrutable intention’.

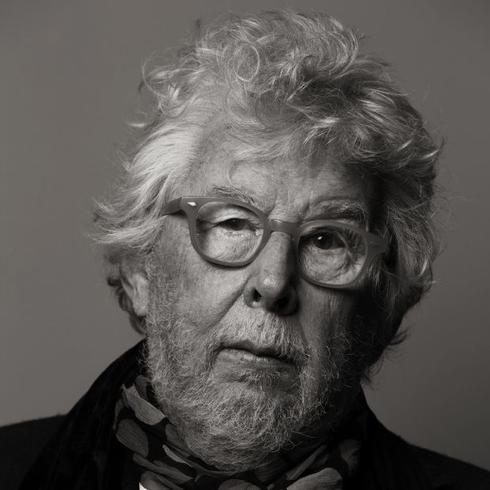

Harrison Birtwistle with David Beard @ 2016