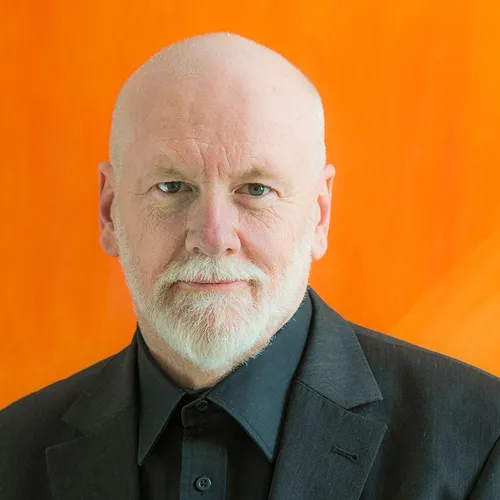

Brett Dean studied in Brisbane before moving to Germany in 1984 where he was a permanent member of the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra for fourteen years. He began composing in 1988, initially concentrating on experimental film and radio projects and as an improvising performer. Dean’s reputation as a composer continued to develop, and it was through works such as his clarinet concerto Ariel's Music (1995), which won an award from the UNESCO International Rostrum of Composers, and Carlo (1997) for strings, sampler and tape, inspired by the music of Carlo Gesualdo, that he gained international recognition. In 2000 Dean returned to his native Australia to concentrate on his composition, and he now shares his time between homes in Melbourne and Berlin.

In 2009 Dean won the Grawemeyer Award for Music Composition for his violin concerto The Lost Art of Letter Writing and in 2016 was awarded the Don Banks Music Award by Australia Council, acknowledging his sustained and significant contribution to Australia’s musical scene. In June 2017 his second opera Hamlet was premiered at Glyndebourne Festival Opera to great acclaim; directed by Neil Armfield with libretto by Matthew Jocelyn and conducted by Vladimir Jurowski.

Dean enjoys a busy performing career as violist and conductor and performs his own Viola Concerto with many of the world’s leading orchestras. Dean notably conducts the BBC Symphony, Los Angeles Philharmonic, Concertgebouw Orchestra, Melbourne Symphony, Sydney Symphony, BBC Philharmonic, Gothenburg Symphony, Toronto Symphony, Tonkünstler-Orchester, Stuttgart Chamber Orchestra and as Artist in Residence with the Swedish Chamber Orchestra.

Dean was 2017/18 Creative Chair at Tonhalle-Orchester Zürich, a role which encompasses conducting, performing and creative programming. Dean also continues as Artist in Residence with Sydney Symphony Orchestra across 2016-2018, and with the Radio Symphony Orchestra Berlin (since 2017).

Other highlights of 2017/18 included three world premieres – the orchestral work Notturno inquieto for the Berlin Philharmonic conducted by Sir Simon Rattle; Approach, a partner work to Brandenburg Concerto No.6 with the Swedish Chamber Orchestra conducted by Thomas Dausgaard; and a duo work for Colin Currie and Håkan Hardenberger, The Scene of the Crime, at Malmo Chamber Festival where he was Composer in Residence. Elsewhere his music has recently been performed by many leading orchestras including the UK tour of Hamlet by Glyndebourne chorus/London Philharmonic Orchestra, Engelsflügel by San Francisco Symphony/Robertson and performances of Testament by Radio Symphony Orchestra Berlin and BBC Philharmonic, Pastoral Symphony by the Aurora Orchestra/Collon.

Brett Dean’s music has been recorded for BIS, Chandos, Warner Classics, ECM Records and ABC Classics, with a new BIS release in 2016 of works including Shadow Music, Testament, Short Stories and Etüdenfest performed by Swedish Chamber Orchestra conducted by Dean. Dean’s Viola Concerto has also been released on BIS with the Sydney Symphony, with Dean reviewed as “a formidable and musical player as well as an impressive composer… an excellent showcase of Dean's range as a composer” (Guardian). Looking ahead a DVD of Hamlet will be released by Glyndebourne.

The concerto is in one uninterrupted movement but can be heard in five major sections:

I. Extremely intimate, yet flowing and playful

The solo cello — in its high register — starts a tentative dialogue with the orchestra through bird-call-like material. While introducing various motivic ideas that will feature throughout the piece, it picks up in density, rhythmic edge, and tempo. Unexpectedly however it dissipates into ...

II. Slow, dreamy, unhurried

An extended slow movement in which the soloist floats above gently undulating wave-like harmonies in harp and divided strings. At its peak, the orchestral colors are dominated by swirls coming from the two contrasting keyboard instruments, piano and Hammond organ. The solo cello takes us gradually down, down, down from its elevated, bird’s-eye-view into the new energy of ...

III. Allegro agitato sempre

In which the various rhythmic components that we’ve heard earlier return with a more demonic and threatening edge, forcing the soloist to “duck and weave” around the orchestra. This wakes the orchestra itself into more volatile actions of its own, in turn pushing the soloist into new territories of repeated down-bow chords and different colorings of the same note. The race comes to a sudden stop and everyone catches their breath for a moment but just when we think a calm may have returned we’re thrown into ...

IV. Fast, rhythmic, relentless

The soloist, now in lowest register, reluctantly takes off again; this cat-and-mouse chase with the orchestra isn’t done yet! At times the orchestra, having taken up the solo-cello’s motivic ideas as their own, then leaves the soloist behind, so keen are they to ride the wave, culminating in an extended orchestral tutti. After it subsides, the soloist returns, hushed, chastened perhaps by the orchestral storm he / she has set in motion. Shadows of former motives lead us to ...

V. Slow, spacious, and still

In the stillness, the soloist tentatively reconnects with the orchestra through a series of extended quarter-tone trills shared with other string soloists in cellos and basses. Calm, distant memories of the cello’s opening bird calls combine with delicate orchestral trills. The work ends with a hushed, upwards-spiraling question mark.

Brett Dean

There is no definitive version of Shakespeare’s Hamlet. There were at least three versions printed within his lifetime or shortly thereafter, and endless variations, including the most commonly used 1st Folio, and an incalculable number of conflated versions.

Our Hamlet relies heavily on Shakespeare’s verse, if not necessarily on the standard chronology of scenes. The opera concentrates primarily on the domestic drama, exploring the depths of Hamlet’s quest for both understanding and revenge, from the death of his father through to his own demise.

This quest is relayed through the fragmentary nature of his relationships with those in his inner circle. It is this very fragmentation – as well as the lack of a definitive text upon which to base the opera – that allows us to explore the most effective and poetically resonant assemblage of story-lines.

Brett Dean